Treasury’s Love Affair with Private Investments Doesn't Add Up

Treasury’s Love Affair with Private Investments Doesn’t Add Up

Two recent, major investigations by

The Oregonian and the

Oregon Journalism Project in

Willamette Week

and statewide local newspapers, recently detailed significant problems with the Oregon State Treasury’s private equity overexposure for PERS.

Following these publications, Divest Oregon has received questions about the information and risks of this exposure, which our coalition has tracked with concern for years. In this memo, we provide answers.

By standard financial yardsticks, Treasury’s private equity investments in the past 13 years routinely underperformed the benchmark long established by the Oregon Investment Council (OIC). They regularly underperformed the broad US stock market. They have not provided exceptional returns. Simply put, Treasury’s love affair with private equity no longer adds up.

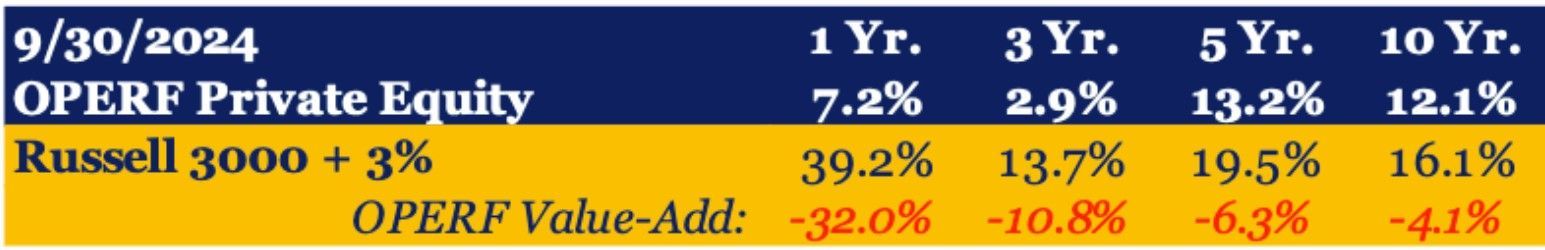

OPERF’s 10-year rolling average private equity returns are substantially below OIC’s benchmark

OIC Investment Policy 1203 (at p.11) says that OPERF's private equity allocation is managed to produce net excess returns “over very long time horizons,

typically rolling, consecutive 10-year periods” (emphasis added).

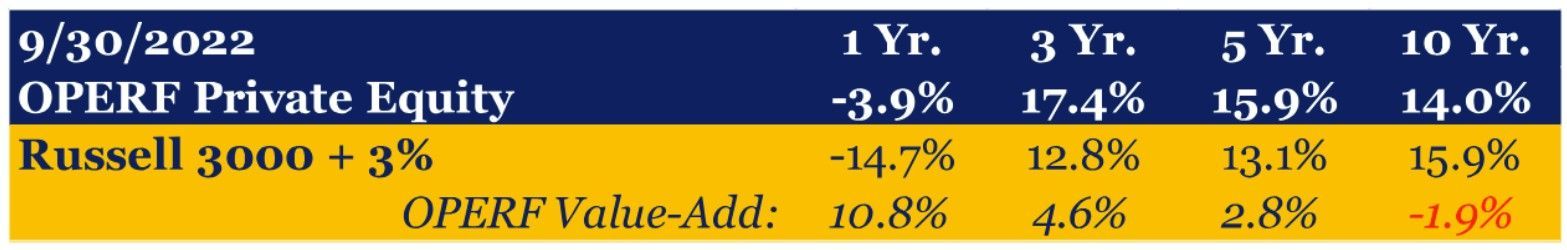

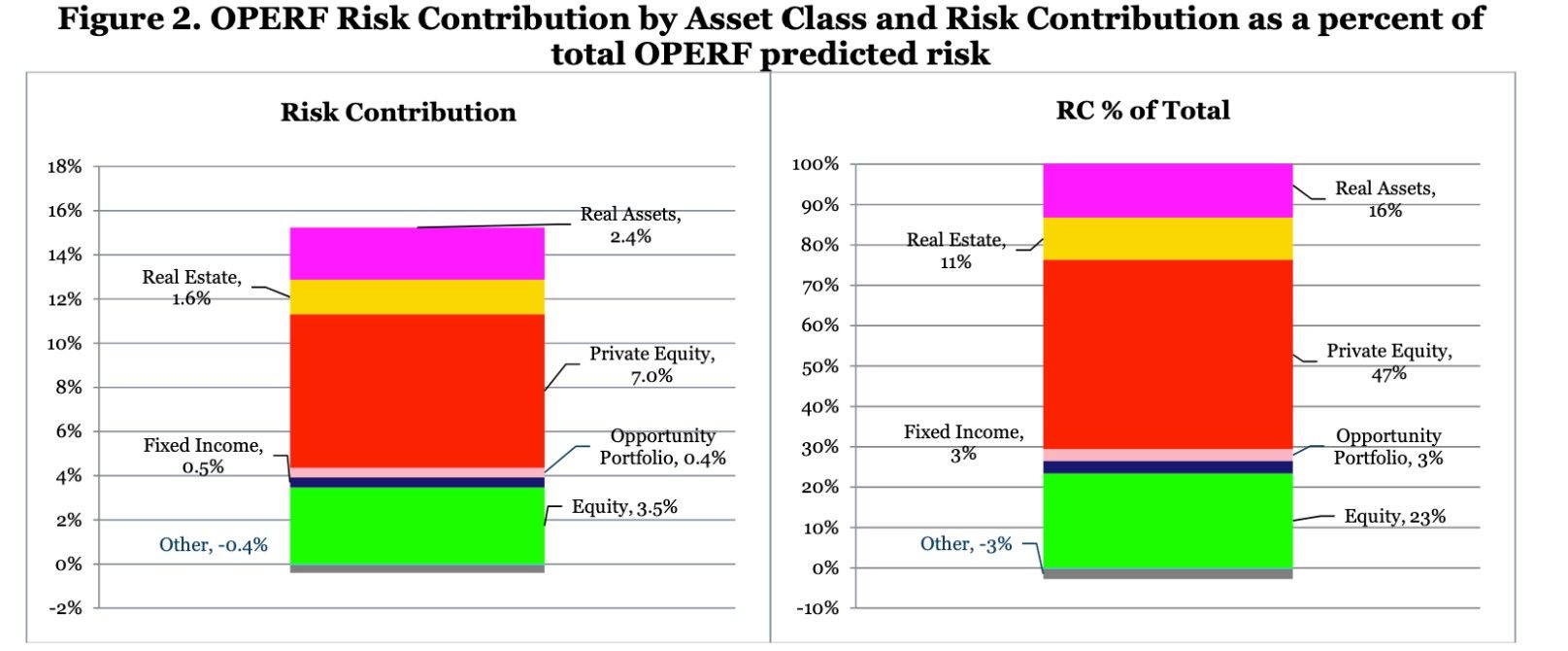

Below are the 1, 3, 5 and 10-year third-quarter private equity rolling returns Treasury presented to the OIC at its

1-22-2025 meeting, at p.59. All OPERF 1, 3, 5 and 10-year rolling returns are below OIC’s benchmark (Russell 3000 stock index + 3%) by substantial amounts, though

Treasury's website at p.9 says 1-year stated returns are not meaningful.

Here is the same data for the previous year, 2023, at p.35. The amount compared to benchmark is slightly positive over 3 and 5 rolling years, and substantially negative over 10 rolling years.

In 2022, the year before that (at p.16), the 3 and 5-year returns are substantially positive, but the 10-year rolling return is substantially negative.

In 2021, the year before that (at p.29), the 5 and 10-year returns are substantially negative.

Note the “IRR” designation of returns above, which means the estimates are of an “Internal Rate of Return.” This is the common method for stating Treasury’s private equity returns. However Treasury's website at p.9 warns: “Due to a number of factors . . . the IRR information in this report DOES NOT accurately reflect the current or expected future returns of the partnership. The IRRs SHOULD NOT be used to assess the investment success of a partnership or to compare returns across partnerships.” (emphasis added).

This points to real problems with how OPERF values its private equity investments. If you are confused about why Treasury would state values in one place that it calls unreliable in another . . . so are we.

Two-thirds of OPERF private equity’s 9 most recent consecutive 5-year rolling averages failed to meet benchmark

In addition to the performance failures documented in the last four consecutive 10-year rolling averages, we were able to calculate the results of the 9 most recent consecutive 5-year rolling averages from data that OIC consultant Meketa presented to the OIC.

The data is annual year-end comparisons of OPERF’s private equity returns with its Russell 3000 index + 3% benchmark, for years 2012 through 2024,

here (p.77)

and here (p.84). Meketa presented the data in OIC meeting materials and Treasury can not disavow them. (Calculation results show some differences with the 1, 3 and 10-year rolling returns presented above. That is because those returns are based on third quarter numbers, not year end numbers.)

The Meketa-presented data allows the calculation of the most recent 9 consecutive rolling 5-year averages: 2012-2016, 2013-2017, 2014-2018, 2015-2019, 2016-2020, 2017-2021, 2018-2022, 2019-2023, and 2020-2024.

The Meketa numbers show OPERF’s private equity returns failed to meet benchmark in 6 of the 9 rolling 5-year averages. In 5 of those 9 averages, private equity even failed to meet the return of the Russell 3000 index—not the 3 percentage points higher which is the standard.

This means OPERF’s private equity performed

worse than a broad US stock market index during more than half the rolling averages examined. That is not high performance as has been so often touted by Treasury management and staff.

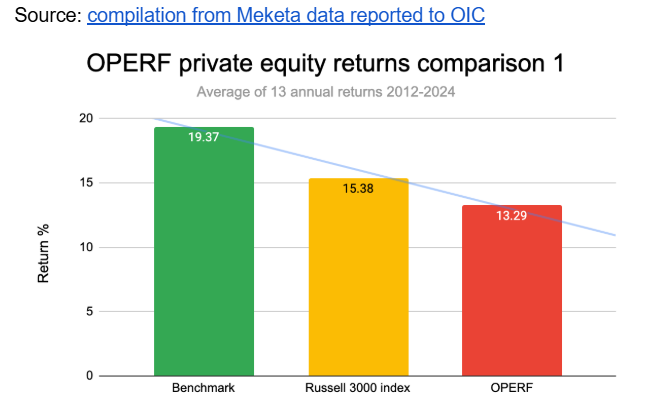

On average over the entire past 13 years, private equity failed to even meet the Russell 3000 index

Tellingly, OPERF’s private equity on average over the entire 13-year period failed to meet benchmark (Russell 3000+3 percentage points) and even failed to meet the Russell 3000 index. According to Meketa’s numbers, OPERF’s private equity average return over 13 years was 13.29%; the Russell 3000 average was 16.37% and the 3% higher benchmark average was 19.37%.

This means

OPERF’s private equity performed worse than a standard stock market index over the entirety of the past 13 years, and underperformed its benchmark by a whopping 31%. Over the past 13 years OPERF would have earned 40% more on the money it put into private equity (3.08% annually x 13 years; 47% with compounding) if Treasury had put its PERS beneficiaries’ money into the standard stock index fund OIC chose as a base for comparison. Instead, staff disregarded policy and continuously steered OPERF into increasing amounts of private equity—with all its overt and covert fees and costs, secrecy, complexity, illiquidity, and economically undesirable and even destructive side effects.

This is a

spreadsheet of our benchmark calculations.

For the past 7 years, Treasury staff disregarded its OIC-mandated investment range for private equity

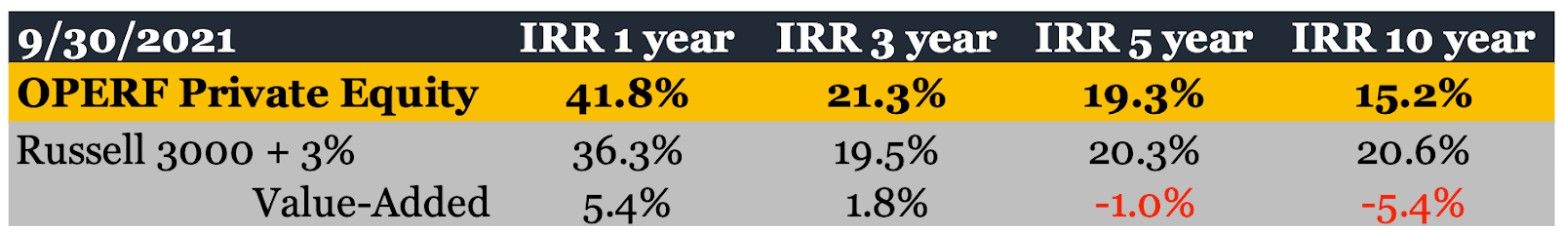

In OIC meetings, Treasury has contended that everything is proper because even though it continues to substantially exceed its target for private equity investments, private equity’s 26.5% share of OPERF is within OIC’s approved “range” of 17.5%-27.5% of OPERF’s portfolio.

Treasury omits saying that ranges are established in order to “balance the desirability of achieving precise target allocations with the various and often material transactions costs associated with . . . rebalancing activities.” (OPERF Investment Policy Statement p.12.)

But there are no transaction costs to slowing the growth of private equity in the portfolio by buying less of it. Transaction costs occur only from sales of existing holdings in the secondary market. And Treasury staff has been pushing the upper range for ever-expanding private equity investments

from 2015 until recent slowed commitments and the $4.5 billion in value- depressing secondary sales reported by

The Oregonian.

OPERF monthly returns and asset allocations, available on Oregon Treasury’s website, show that in 2018 the OIC-approved range for private equity in OPERF was 13.5% to 21.5%—the target of 17.5%, plus or minus 4%. They further show that staff exceeded that range in the fourth quarter of 2018 when OPERF had 22.1% of its portfolio in private equity.

For the next 3 years, in every quarter but one, Treasury management allowed staff to exceed its OIC-approved private equity range. By the third quarter of 2021, OPERF was almost 9 percentage points above its target and 5 percentage points above its upper range.

There were no real brakes on this growth. In the fourth quarter of 2021 OPERF’s private equity came within the upper range–but only because the OIC increased the upper range from 21.5% to 27.5%. And the new private equity range, unique among OPERF asset classes at the time, was itself imbalanced. Rather than plus or minus the same number around the target, the OIC skewed the range to be 7.5 percentage points above the increased 20% target, and 5 percentage points below it (as graphically represented in the figure below). The accommodation to staff’s profligacy is obvious.

Treasury remained resistant to lowering allocations even as the problem of misallocation loomed.

At a November 2022 OIC meeting, Treasury management sought to solve the misallocation problem by again raising the private equity target, from 20% to 22%. After Chair Samples expressed her disapproval,

management said (at 58:45) “I could tell you candidly whether it's 20 or 22 it makes no difference to us. We’re still going to be executing the same plan.” At the OIC’s January 2023 meeting,

management described (at 1:26:30) OIC’s private equity policy target as “artificial”: “I don’t think we as an organization are in a rush to get down to 20 percent. We hope to get there in time, but understanding what you’re saying, your question, we don’t want to lose the long term value of what we're doing in order to get to

some 20% artificial number.”

From October 2018 through September 2021, Treasury management allowed private equity to exceed the upper range of OIC approval in 11 of 12 quarters. After the OIC then increased the upper range, Treasury management and staff still exceeded it in 7 of 15 quarters. And if the OIC in 2021 had approved a range of plus or minus 5 percentage points from target—the balanced practice it usually followed—then OPERF private equity would have been

beyond the upper range in all quarters but one for the past seven years—from October 2018 until today.

Management and staff should have taken OIC policy seriously.

The signals to start a responsible path to target were readily apparent in 2015. Instead, Treasury waited

eight more years

for the bottom to fall out of OPERF’s excessive private equity investments in 2023.

While no one can always predict the behavior of future investment markets, anyone can predict that damage to pensions should be expected when pension investment policy is disregarded for years.

Had Treasury simply followed policy, rather than disregarding it, OPERF would not have incurred the $1.4 billion investment loss calculated by the Oregon Journalism Project and published in

Willamette Week.

This table shows Treasury management’s and staff’s disregard of private equity’s upper ranges from 2018-2025.

Treasury management defends its serial policy violations as good for OPERF. They’re not.

The Oregonian quoted Treasury’s chief investment officer as saying that longstanding OIC policy expecting 3% above-market performance from high-risk private equity returns “may not be the best measure.” He contended that over the last 20 years, OPERF’s private equity outperformed the stock market by 2 percentage points and he suspected the OIC would be happy with that—even though that is a 33% reduction in OIC’s policy—expected market outperformance for private equity.

These comments do not inspire confidence that Treasury management is facing reality. The facts speak for themselves: Seven years of serial policy violations by investment staff that resulted in today’s $1.4 billion loss, and a private equity 13-year average that performed worse than the broad US stock market—making Treasury's high-fee, high-risk, illiquid bets costly losers, not index-beating winners.

OPERF’s heavy reliance on private investments raises important policy questions:

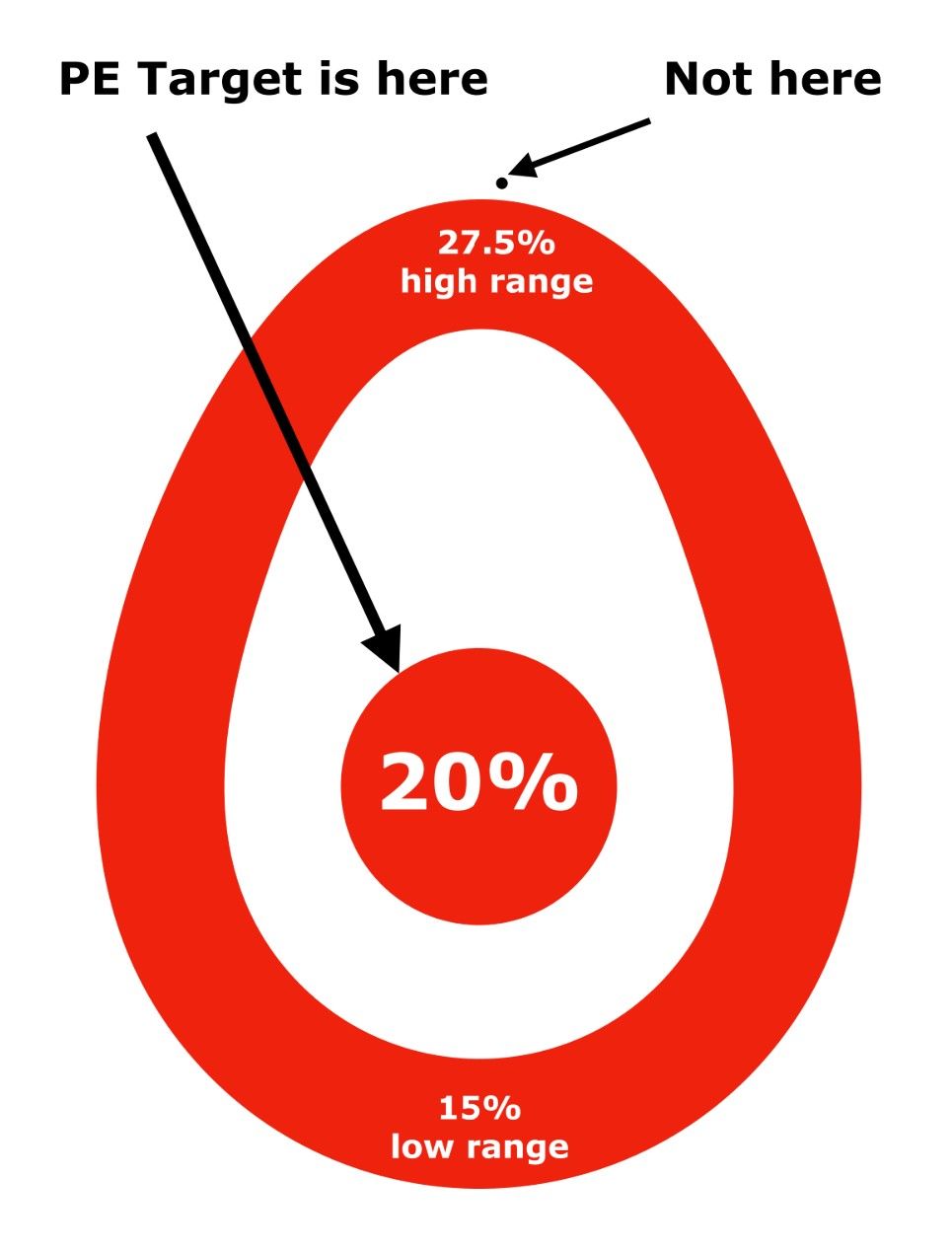

Should a responsible public pension fund invest a quarter of its assets into a class that generates almost half of all financial risk to the portfolio? That is the risk Treasury reports to the OIC (March 2025, p.102), as seen in OST’s presentation chart at below right.

Should a responsible public pension fund invest almost 60% of its assets in opaque private investments with no public oversight? OPERF is out on a limb in this regard. Public Plans Data, an independent academic and professional consortium, reports that in 2024, state and local pensions averaged about half the amount of private equity (13.7%) as OPERF has, as well as about half the amount of overall private investments (30-33%). And a 2024 survey of 50 top pension executives found that most thought a 20-40% allocation to private assets was reasonable—while none thought more than 50% was reasonable.

Treasury’s disregard of OIC allocation policy is not limited to private equity.

Treasury’s Real Assets class, another set of secretive private investments, comprises 10.5% of OPERF, even though its target is 7.5% and its approved upper range is 10%. That puts it 40% over target, and over its top permissible range. Staff tells the OIC (at p.68) it does not expect to bring the allocation to target until 2032—7 years from now. And as seen from Treasury’s Risk Contribution chart above right, Real Assets is also an outsized risk contributor—with 10.5% of OPERF assets, it generates 16% of portfolio financial risk.

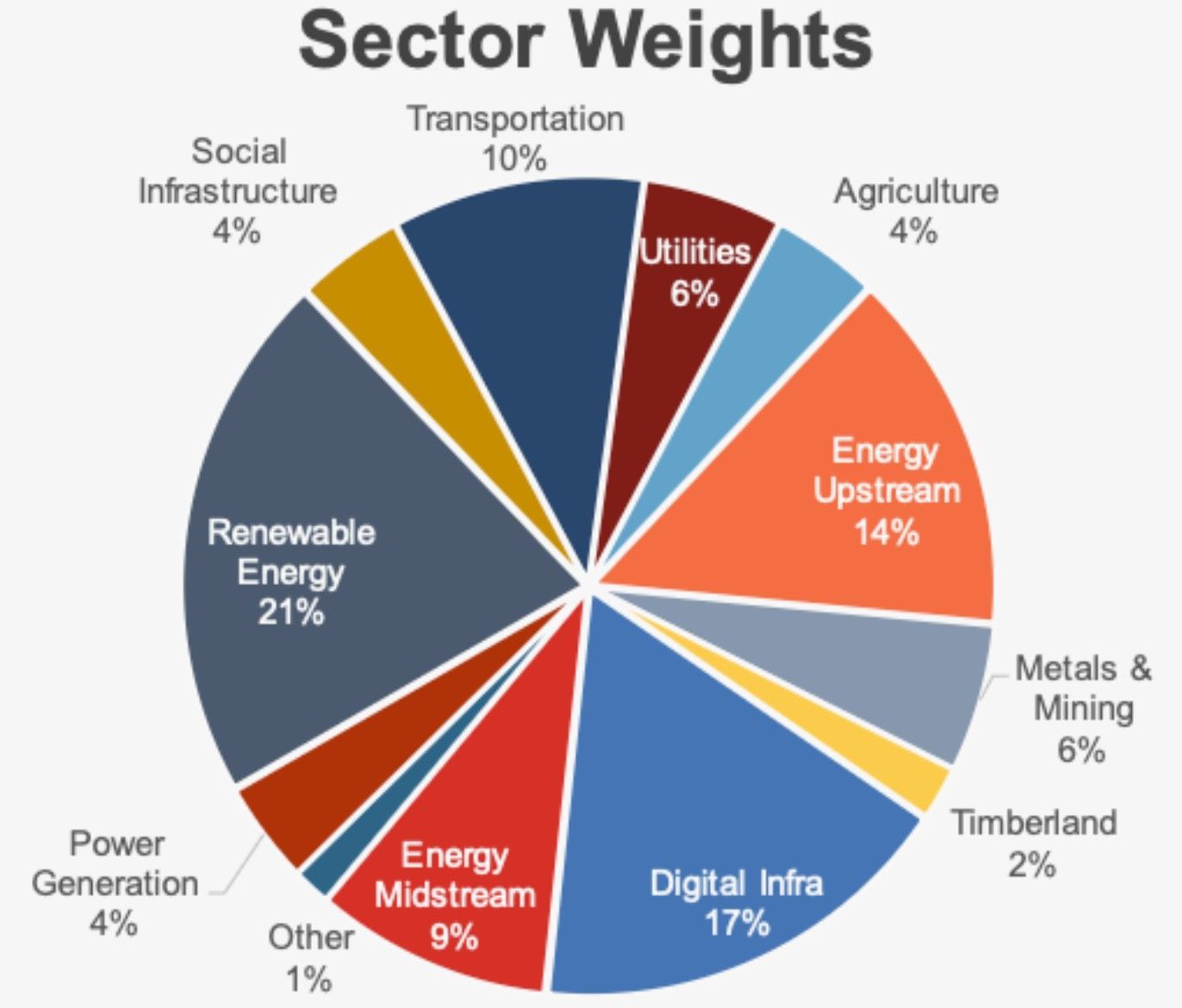

At least as importantly, much of PERS emissions intensity comes from the Real Assets class. That must be addressed immediately. As shown above from Treasury’s April 2025 presentation to the OIC (at p.54), about one third of these assets are in sectors funding fossil fuel extraction, infrastructure, and power generation.

These OPERF investments create and cement decades-long greenhouse gas emissions. They will inevitably increase global warming that

economists now identify (at pp.15-20) as posing increasingly substantial risks to GDP and investment values.

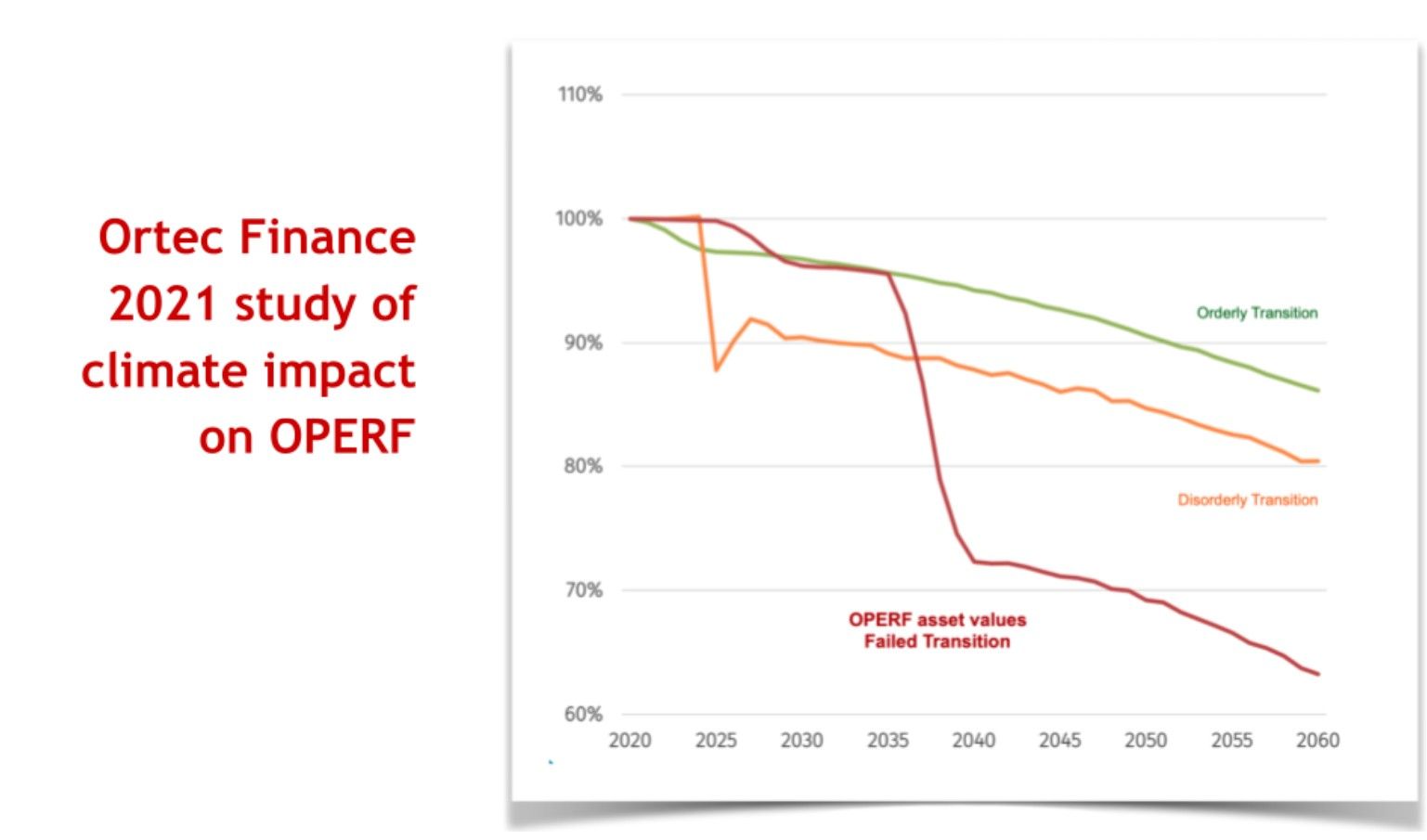

As shown below, Treasury’s consultant Ortec (in its 2021

Climate Scan Report at p.8) forecast a 37% reduction in OPERF values by 2060 under a failed transition—the path for which OPERF is currently investing.

OST’s climate investment choices, along with other public pension funds, matter considerably to their own future returns and to future retirees.

Treasury staff nevertheless ignores this substantial climate risk, and claims a history of Real Asset returns 1-2% over benchmark, presenting (at p.66) to the OIC this April an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 7.6% from inception of

the asset class to date. However, Treasury’s website says “IRRs SHOULD NOT be used to assess the investment success of a partnership or to compare returns across partnerships.” More accurate information on Treasury’s website shows Real Asset returns to be 4.8% from inception to date on a time-weighted basis. This 4.8% is almost 2% below benchmark.

Conclusion: An unremedied problem in Treasury’s investment culture will continue to cost PERS billions. It will also sink the Net Zero Plan for OPERF.

Treasury’s own numbers belie the contention that private equity is a high-performing asset that is worth its high risk, complexity, secrecy and illiquidity. In the past, perhaps yes, but the past is over. Experts agree that high interest rates and too much money dedicated to too many marketers from firms chasing too few deals have drastically changed the attractiveness of private equity. Simply put, Treasury management is driving private equity investment by looking in the rearview mirror.

But the problem at Treasury is more than bureaucratic inertia. Years of ingrained conduct by Treasury management and staff show they have resisted and even flouted OIC investment policy when they want. Recent news investigations pulled the curtain on a troubling and problematic investment culture in need of serious reform.

Without reform to overcome active staff resistance to policy, PERS will not just continue to leave billions on the table. The future of the Treasurer’s Net Zero Plan, and the climate-protecting investment changes that must come from it, are in grave doubt. Prominently hanging in the balance is an end to new private investments in decades of climate-damaging fossil fuel projects and infrastructure. This was a promise made by the previous Treasurer in the Net Zero Plan, and made by the current Treasurer on the campaign trail.

It is time for those promises to show themselves in action–beginning with a complete and public examination of how and why Treasury management and staff spent the better part of the past 10 years disregarding OIC policy on private equity investing.

Oregon State Treasury should engage or divest from companies fueling a new era of resource conflicts