Oregon State Treasury should engage or divest from companies fueling a new era of resource conflicts

Thanks to the passage of CRIA and the Coal Act, Oregon is moving toward a more transparent assessment of climate-related risks, engaging with asset managers and companies, and identifying climate-positive investments.

OPERF has nearly $90 million invested with Exxon, $40 million in Chevron, and $5 million in Shell. Can the Treasury hold these companies accountable and protect the wider portfolio from major conflict exposure?

Following is incisive testimony to the January 2026 Oregon Investment Council by Andrew Bogrand, Divest Oregon’s volunteer Communications Director.

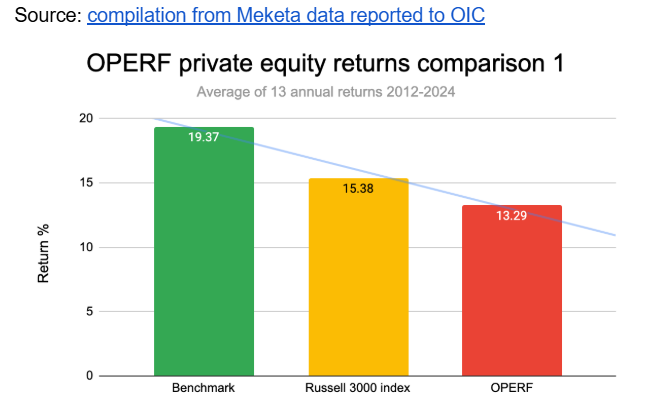

For over five years, the Divest Oregon coalition has encouraged the Oregon State Treasury to take seriously the financial risks associated with fossil fuel investments, particularly within the context of the wider energy transition.

Treasury, as well as the Oregon Investment Council, has listened and responded. Thanks to the 2025 Climate Resilient Investment Act (CRIA) and the 2024 Clean Oregon Asset Legislation (COAL) Act, our state is moving toward a more transparent assessment of climate-related risks, engaging with asset managers and companies, and identifying climate-positive investments.

Of course, much of the work remains.

In the spring of 2025, Divest Oregon provided testimony to lawmakers in Salem about the coalition’s support of CRIA. We shared how the bill would help Treasury address “new economic realities, where geopolitical contestation…and natural resource competition will upend the financial logic of passive investing.”

A year later, this statement rings painfully true. We stand on the precipice of resource-driven conflicts in Venezuela, Greenland, and Iran. We are witnessing a deterioration of the international rules-based order, which will come with serious financial implications.

This breakdown is not random. Chevron has played “the long game” in Venezuela, spending millions lobbying the Trump administration and positioning itself to profit following the US invasion. Shell is seeking a multi-billion gas project following the illegal ouster of President Maduro, which presumably also secured ExxonMobil’s interests – not in Venezuela, but in neighboring Guyana. And, the American Petroleum Institute, an industry lobby group including Chevron, Shell, and Exxon, recently pledged to “stabilize Iran” if the regime is ousted there, too.

Of course, whether these companies will profit from this new era of resource colonialism remains unclear. Darren Woods, the CEO of ExxonMobil, said bluntly that Venezuela is “un-investable.” Chevron has also acknowledged that any future work in Venezuela will require extensive guarantees and long-term stability, conditions which remain absent. Despite all the money spent on lobbying, the oil market remains volatile and these companies will likely seek taxpayer support and sanctions relief for risky bets abroad

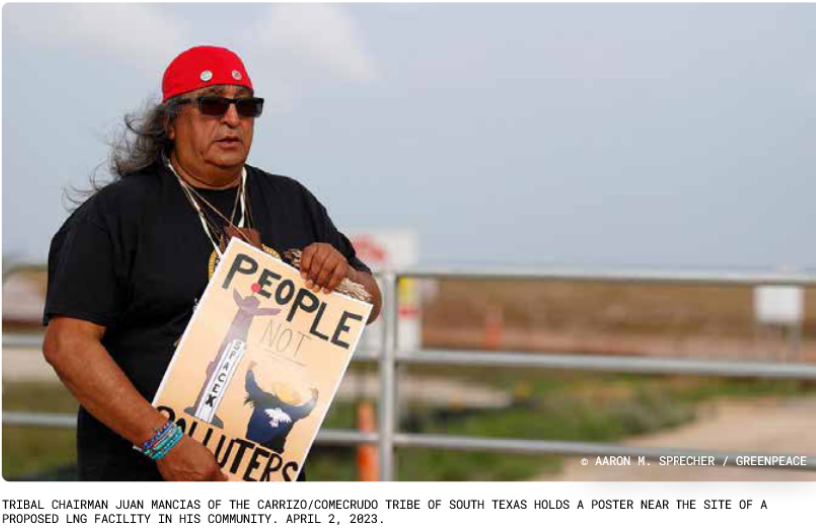

Treasury has nearly $90 million invested with Exxon, nearly $40 million in Chevron, and over $5 million in Shell. Now the question is how to hold these companies accountable and protect the wider portfolio from major conflict exposure.

Not all energy companies are equal. In contrast to Chevron, France’s TotalEnergies, which Treasury also owns, has no intention to enter Venezuela despite its operations in nearby Suriname, presumably worried that their presence could make a humanitarian crisis worse or even directly fund human rights violations.

If Treasury is serious about engagement, as set forth in CRIA, now is the time to exercise this commitment toward the most politically-exposed companies. Extraction by military force pushes the absolute boundaries of the social license to operate and undermines other holdings in Treasury’s portfolio.

Companies have a major and well-recognized responsibility to avoid contributing to war. This responsibility is rooted in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights as well as in international humanitarian law. Companies are expected to conduct rigorous human rights due diligence to ensure that their operations, supply chains, and technology do not fuel or contribute to conflict.

If companies like Chevron and Exxon fail to respond to engagement along these lines then divestment is both an appropriate business decision -- and the right thing to do.